MIGRATION IN EUROPE

A brief history

INTRODUCTION

A brief history

INTRODUCTION

There are nearly one billion migrants in the world. Three quarters of them move within their country. And among those who migrate abroad, less than 30% are moving from a developing to a developed country.

For centuries, Europe was a land of departure to the Crusades, to the colonies, in the New World, for religious missions or international trade. Nowadays it has become a continent of immigration. Since centuries, European identity has been constructed by a permanent contact with other cultures. Immigration in Europe, however, is marked by the history of each of its member countries.

The 27-EU has 490 million inhabitants; more than 25 million are foreigners, some coming from outside Europe.

Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece have become countries of immigration, especially from the neighbouring countries (Albanians, Tunisians, Moroccans, Romanians, etc.).

Even if nowadays there is freedom of movement for all European citizens in its territory, the Europeans are not very mobile: only 5 million people live in a foreign country that is only 1.5% of the people in working age. But this percentage has been rising since the last entry of 10 new countries in the EU (ex. Poland, Romania and Bulgaria).

MIGRATION IN FRANCE

Between 1850 and 1950, France was among the first and most important immigration countries in Europe, because of the population decline, which began in the late eighteenth century, which led to shortages of labour force and soldiers. It had 380 000 foreigners in 1851, when the first census that distinguished the French and foreigners, one million at the beginning of the twentieth and three million in 1930. Since 1999, the number of foreigners (3.5 million people without French nationality) is distinct from that of immigrants (4 million people), with or without French nationality. They represent 7% of total population. A quarter of French people have a foreign grand-parent.

In the 1820s, France was the second most popular destination for European immigrants, after the United States (60 000 German in Paris in 1848 for example). The 1889 Act seeks to make foreigners French, entitling the nationality law of the soil for newcomers.

Before 1914, 90% of the migrants were from neighbouring countries. Many came for seasonal activities. In 1911, there were 1 160000 foreigners in France with 1/3 Italian and 1/4 Belgian, so approximately 3% of the total population.

In the 1920s, the French government concluded an agreement on workers with Poland, Italy and Czechoslovakia. Following a wave of xenophobia, and the economic crisis, France suspends immigration in 1932, before the Vichy laws of 1940, which led to the exclusion of foreigners and Jews.

Before 1939:

In Europe, the revolutions against monarchies, totalitarian regimes caused major population movements. The political or economic exiles took refuge in France, which was the symbol of freedom after the Revolution.

Belgians, Germans, Spaniards, Swiss, etc. came to work in France with the industrial revolution that required a lot of jobs. In 1866, Belgian immigrants were the most numerous.

In 1881, there were one million immigrants in France, because the birth rate decreased in contrast to other European countries. Some came to seek work in the flourishing industry or to escape poverty or persecution.

From 1900, the Italians became the majority. At that time immigrants were unpopular, especially the Italians and the Belgians, and filled the most difficult and least paid jobs.

During the Great War, colonial troops were sent to the front and the Belgian refugees were used as labor force for the arms industry. There were not enough workers and France used colonial workers (often by force), who were victims of racism and exclusion.

After World War I, France was in need of labour force to compensate for the 1.3 million deaths. A strong immigration happened and therefore the number of immigrants in France doubled in 10 years (the largest increase ever seen!). The immigrants came mainly from Poland, Russia, Turkey (new immigrants) and Italy (marked by the takeover of Mussolini), who remained the majority. There was also an increase of colonial immigration.

With the crisis of 1931, xenophobia (attenuated during previous years) increased, migrants were increasingly used for hard labour and some returned to their country. The anti-Nazis from Germany and the Jews fled because of the persecution.

The three decades of prosperity (1945-1975): the cycle of "migrant workers”

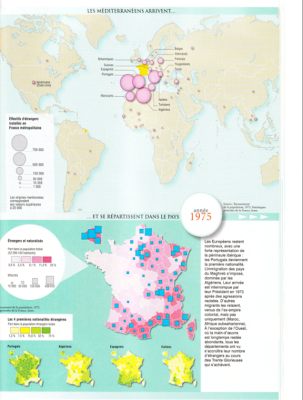

After the Second World War, for economic purposes, France experienced a new wave of mass immigration, organized by the State: Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese. The 1960s marked the beginning of Algerian, Moroccan, Tunisian, Turkish and Yugoslav immigration.

The state conducted a real migration policy with the creation of the National Immigration Office (ONI). It had the monopoly of the introduction of foreign workers. However, the real growth cycle began 10 years later when the economy took off and when conscripts were mobilized in Algeria.

During the 60s, agreements were signed with an increasing number of countries (Spain, Morocco, Tunisia, Yugoslavia, Turkey, etc.). The highlight was the arrival of thousands of illegal Portuguese (760 000 Portuguese in France in 1975). But France “accepted” the Portuguese to limit the number of Algerians.

Since 1975 the history of immigration, however, is linked with colonial history and opens to Africa. The African flows grow with decolonization, especially the “pieds noirs” (one million) and “Harkis”, who are excluded and are forced to live in slums. Two thirds of immigrants are working in industry, mining or constructions and are poorly paid.

Following the economic crisis of the 70s, France suspended working immigration again in 1974, but allowed the family regrouping. From 1976, she tried unsuccessfully to encourage the return of immigrants to the countries of origin. Immigration continues with feminizing, and new generations of immigrant appeared.

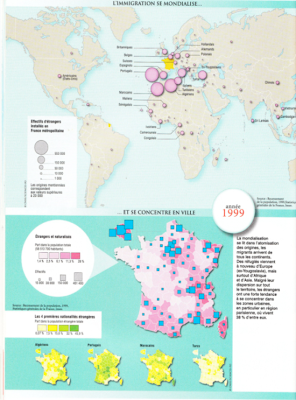

In 2004, immigration flows were predominantly of Africans for about 2/3 (Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa), followed by Europe, America, Asia and Oceania.

The migration has continued since 1975 and changed. Inflows of workers have followed the waves of refugees and family migration. Family reunification, suspended in 1974, was restored in 1976. This is to re-balance the ratio of women/men for immigration settlement.

Evolution of foreign origin in France from 1946 to 1999 (in thousands)

1946 | 1954 | 1962 | 1968 | 1975 | 1982 | 1990 | 1999 | |

Spanish | 302 | 289 | 442 | 607 | 497 | 327 | 216 | 160 |

Italians | 451 | 508 | 629 | 572 | 463 | 340 | 253 | 201 |

Polish | 423 | 269 | 177 | 132 | 94 | 65 | 47 | 34 |

Portuguese | 22 | 20 | 50 | 296 | 759 | 767 | 650 | 555 |

Algerian | 22 | 212 | 350 | 474 | 711 | 805 | 614 | 475 |

Moroccan | 16 | 11 | 33 | 84 | 260 | 441 | 573 | 506 |

Tunisian | 2 | 5 | 27 | 61 | 140 | 191 | 206 | 154 |

Other African | 13 | 2 | 18 | 33 | 82 | 158 | 240 | 283 |

Asian | 70 | 41 | 37 | 45 | 104 | 290 | 425 | 410 |

Turkish | 8 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 51 | 122 | 198 | 206 |

Yugoslav | 21 | 17 | 21 | 48 | 70 | 62 | 52 | 50 |

Russian | 51 | 34 | 26 | 19 | 12 | 7 | 5 | 13 |

K. Akoka: Migrants d’ici et d’ailleurs, du transnational au local, Poitiers 2009

Refugees, whose number has risen from 2.5 million in 1975 to 25 million by 2005 in the world, were initially well- received in France, at the beginning from Chile and the Southeastern Asia, and after other parts of the world (African Tamils, Kurds, Iraqis, Afghans, Eastern Europeans). Between 1999 and 2004, a quarter of immigrants came from the EU 25.

Today, laws are more restrictive because of the fear of Islamism, the fight against the illegal migration and racist pressure. In this context, the situation of the Paperless immigrants appeared, for over 10 years, in all the headlines.

Without being the European country where the rate of foreigners is the strongest because France is a country where the composition of the population is the most diverse today.

Emigration

Expatriation is growing: more and more French young people are trying their luck abroad. Moreover, these expatriates settle permanently in their host countries. (See maps below)

Bibliography

Atlas mondial des migrations - Ed. Autrement, 2009

Bozarslan, Hamit – „Le brasier oublié du Moyen-Orient”, Ed. Autrement, 2009

Immigrés et étrangers - Observatoire des inégalités, Mars 2009

La France au pluriel - Les Cahiers Français n° 352, 2009

Les routes de l'humanité – Ed. Le Monde, revue hors série, 2008/2009

Migratins, métissage, une France autrement - Le Mook, Ed. Autrement, 2008

Noiriel, Gérard – „Immigration, antisémitisme et racisme en France: discours publics, humiliations privées”, Ed. Hachette, 2009

Petit guide pour comprendre les migrations internationales - La Cimade, 2009

Population et Société, n°452 – INED, 2009

No comments:

Post a Comment