MIGRATION IN THE CZECH REPUBLIC

Legend about the foundation of Czech land

According to myth, some Slavic people from an area between the Vistula River and Carpathian mountains set off in search of plentiful lands to the west. Forefather Čech and his brother, Lech, led them. After a long time (maybe years) traveling, they arrived to busky land.

Forefather Čech climbed Říp mountain and looked around the land. Then, he allegedly said: "Oh, comrades, you endured hardships along with me, when we wandered in impassable woods; finally we arrived at our homeland. This is the best country predestined for you. Here you will not miss anything, but you will take pleasure of permanent safety. Now that this sweet and beautiful land is in your hands, think up suitable name".

The Bohemians named their homeland after their leader and forefather, Čechy. Čech means "one of us". Touched, Čech replied: "God bless our Promised Land, by thousands fold wishes wishful from us, save us scathe-less and breed our issue from generation to generation, amen".

Čech has been duke of his land for a long a time. There was peace in his land, nobody thieved, etc. But after Čech's death, morals hardly worsened.

The most famous Czech people

John Amos Comenius – Jan Amos Komenský

J. A. Comenius was a Moravian teacher, educator and writer. He was the last prelate of Jednota bratrská.

He started to study at Strážnice after his parents and two sisters died. He attended the Latinschool in Přerov, Moravia, where he returned 1614-1618 as a teacher of the school.

He continued his studies in Herborn (1611-13) and Heidelberg (1613-14). Comenius became a pastor at age 24 and led the Brethren into exile when the Protestants were persecuted under the Counter Reformation.

He lived and worked in many different countries in Europe, including Sweden, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Transylvania, the Holly Roman Empire, England, the Netherlands, and Royal Hungary. Comenius took refuge in Leszno in Poland, where he led the gymnasium, then moved to Sweden to work with Queen Christina and the chancellor Axel Oxenstierna.

From 1642-1648 he went to Elbing in Polish Royal Prussia, then to England with the aid of Samuel Hartlib, who came originally from Elbing. In 1650 Zsuzsanna Lorántffy, widow of George I Rákóczi, prince of Transylvania, invited him to Sárospatak. Comenius remained there until 1654 as professor in the first Hungarian Protestant college ; he wrote some of his most important works there. Comenius returned to Leszno.

During the Northern Wars in 1655, he declared his support for the Protestant Swedish side, for which his house, his manuscripts, and the school's printing press were burned down by Polish partisans in 1656. From there he took refuge in Amsterdam in the Netherlands, where he died in 1670. For unclear reasons he was buried in Naarden, where his grave can be visited in the mausoleum dedicated to him.

Comenius, his life and teachings, have become better known since the fall of the Iron Curtain. His book, Labyrinth of the World and Paradise of the Heart, is actually a reflection on his life experiences. Other works include Janua Linguarum Reserata and Orbis Sensualium Pictus (World in Pictures) (1657), probably the most renowned and most widely circulated of school textbooks, and the Protestant Hymn songbooks.

According to Cotton Mather , Comenius was asked to be the president of Harvard University, but moved to Sweden instead. He also attempted to design a language in which false statements were inexpressible.

Václav Havel

Václav Havel (born October 5, 1936, in Czechoslovakia) is a Czech playwright, essayist, former dissident and politician. He was the tenth and last President of Czechoslovakia (1989–1992) and the first President of the Czech Republic (1993–2003). He has written over twenty plays and numerous non-fiction works, translated internationally. He has received the US Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Philadelphia Liberty Medal, the Order of Canada, and the Ambassador of Conscience Award. He was also voted fourth in Prospect Magazine's 2005 global poll of the world's top 100 intellectuals.

Beginning in the 1960s, his work turned to focus on the politics of Czechoslovakia. After the Prague Spring, he became increasingly active. In 1977, his involvement with the human rights manifesto Charter 77 brought him international fame as the leader of the opposition in Czechoslovakia; it also led to his imprisonment. The 1989 "Velvet Revolution" launched Havel into the presidency. In this role, he led Czechoslovakia and later the Czech Republic to multi-party democracy. His thirteen years in office saw radical change in his nation, including its split with Slovakia, which Havel opposed, its accession into NATO and start of the negotiations for membership in the European Union, which was attained in 2004.

Miloš Forman

Jan Tomáš Forman, (born February 18, 1932), better known as Miloš Forman, is a Czech film director, screenwriter, actor and professor. Two of his films, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest and Amadeus, are among the most celebrated in the history of film, both garnering him the Academy Award as a director. He was also nominated for The People vs. Larry Flynt.

Forman was born in Čáslav, Czechoslovakia (present-day Czech Republic), the son of Anna Nesvadbová, who ran a summer hotel, and Rudolf Forman, a professor. His parents were Protestants; his father was arrested for

distributing banned books during the Nazi occupation and died in Buchenwald in 1944, and his mother died in Auschwitz in 1943.

Forman lived with relatives during World War II and later discovered that his biological father was a Jewish architect. After the war, Forman attended King George College public school in the spa town Poděbrady, where his fellow students were Václav Havel and the Mašín brothers. Later on, he studied screenwriting at the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague.

Forman directed several Czech comedies in Czechoslovakia. However, in 1968 when the USSR and its Warsaw Pact allies invaded the country to end the Prague Spring, he was in Paris negotiating for the production of his first American film. The Czech studio for which he worked fired him, claiming that he was out of the country illegally. He moved to New York, where he later became a professor of film at Columbia University and co-chair (with his former teacher František Daniel) of Columbia's film division. One of his protégés was the future director James Mangold, whom Forman had advised about scriptwriting.

In spite of initial difficulties, he started directing in his new home country, and achieved success in 1975 with the adaptation of Ken Kesey's novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, which won five Academy Awards including one for direction. In 1977, he became a naturalized citizen of the United States. Other notable successes have been Amadeus, which won eight Academy Awards, and The People vs. Larry Flynt, for which he received a Best Director Academy Award Nomination and a Golden Globe win.

Josef Škvorecký

Josef Škvorecký, (born September 27, 1924) in Náchod, Czechoslovakia, now Czech Republic, is a leading contemporary Czech writer and publisher who has spent much of his life in Canada. He and his wife were long-time supporters of Czech dissident writers before the fall of communism in that country. By turns humorous, wise, eloquent and humanistic, Škvorecký's fiction deals with several themes: the horrors of totalitarianism and repression, the expatriate experience, the miracle of jazz. Škvorecký graduated in 1943 from the Reálné gymnasium in his native Náchod.

During the Second World War, he spent two years as a slave laborer in a German aircraft factory. After the war, he started studying at the Faculty of Medicine of Charles University in Prague. After his first term, he moved to the Faculty of Arts, where he studied English and Philosophy, receiving his Ph.D. in Philosophy in 1951. Between 1952 and 1954, he performed his military service in the Czechoslovak army.

He worked briefly as a teacher, editor and translator during the 1950s. During this time, he finished several novels including The End of the Nylon Age and The Cowards. When they were published in 1956-1958, they were immediately condemned and banned by the Communist party. His prose style, open-ended and improvisational, was an innovation, but this and his democratic ideals were a challenge to the prevailing socialist regime. Škvorecký kept writing, and helped nurture the democratic movement that culminated in the Prague Spring in 1968.

After the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia that year, Škvorecký and his wife, writer and actress Zdena Salivarová, fled to Canada.

In 1971, he and his wife founded 68 Publishers which, over the next twenty years, published banned Czech and Slovak books. The imprint became an important mouthpiece for dissident writers, such as Václav Havel, Milan Kundera, and Ludvík Vaculík, among many others.

HISTORY OF MIGRATION

From the 17th century to the First World War

From the 17th century to the First World War

Significant wave of emigration followed past the violent political and religious changes, such as the Hussite period and especially after the defeat of the Estates Uprising in 1620 and after the introduction of the Renewed Land Constitution (obnovené zřízení zemské) in 1627.

Another type of relatively massive emigration for economic reasons came as a result of demographic growth and the lack of land in the second half of the 19th century. Czech and Slovak emigrants left the U.S. in particular, but also in Russia and other countries.

Large waves of emigration for religious reasons have brought civil and religious wars 16th and 17th century (e.g., the Jews from Spain, the Czech non-Catholics, Huguenots from France after 1685, religious emigrants from Great Britain to North America, etc.).

The 19th century was a period of mass migration to the U.S., particularly from Ireland, Germany, Italy, Poland and other countries. Mass political exile following the Russian revolution in the years 1918-1923 after the Nazis seized power in Germany in 1933. In particular, the emigration of Jews before the war and the war would have significant implications for the subsequent rise of cultural and scientific in the USA.

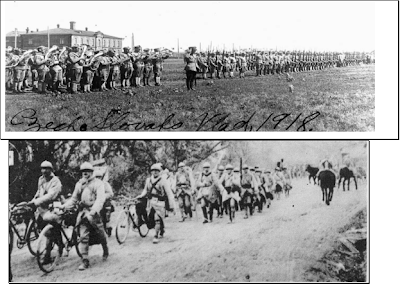

Czechoslovak Legions

In World War I, many Czechoslovaks had to immigrate to Russia, Italy and France. They had to fight against Germany and they were used as spies. Either they had to control Siberia in Russia. However, due to the evolution of events they had to immigrate to America and back to Czechoslovakia. By the end of 1918, they joined the Czechoslovak legions in Russia about 61000 soldiers and of these 61 000 soldiers died something about 4500. They were one of the most important squad in Russia. Thanks to those was established a peace.

In 1918 was founded the Czechoslovak Brigade in France which had 9600 soldiers and died 650 Czech legionnaires. Either 60000 soldiers had to immigrate to Italy and had to fight against Czechoslovak soldiers in Austro-Hungarian Army. Three hundred fifty men died there.

In 1929, many Czechoslovak people had to immigrate to the USA, due bad financial situation all over the world. It was mostly businesspersons and traders, who saw hope in the U.S.

Emigration in the Second World War

The first emigration in Czechoslovakia was caused by the occupation of Nazis in 1939. The emigrants were politicians, artists and Jews because of the holocaust. Lots of them were fighting in foreign forces, and lots of them came back after the war.

One of the famous emigrants from our country was an actor, dramatist and writer Jan Werich, who stayed in the USA with J. Voskovec and Jaroslav Ježek during the Second World War – they did not want to conform with their work to the rules of the war.

Migration in the Czechoslovakia

After the period following the end of World War II (1945-1947) saw massive population movements, both across and within the borders of Czechoslovakia. Although exact data for the period are not available, it is estimated that over five million people were on the move, including about four million in the Czech lands. The migration losses from the Czech areas in those years amounted to about 2.7 million people. In addition, from 1945 to 1947, around 2.5 million German settlers returned to Germany and Austria. Some 90,000 Hungarians also returned to Hungary from Slovakia, while about 50,000 people were forcefully displaced from Czechoslovakia to Ukraine and other parts of the former USSR.

Conversely, during the period 1954-1950, about 220,000 people of Czech or Slovak origin returned from abroad. These returning migrants headed in particular for the border regions, which had been depopulated by the transfer of Germans.

Another specific wave of post-war immigration struck Czechoslovakia immediately after the war, when some 42,000 people immigrated to Czechoslovakia from Ukraine, nearly 40,000 from the Volnynia region.

The 1948 -1989 period

During the 1948-1989 periods, waves of emigration tended to follow political changes in the country. The Communist coup d’état in 1948 resulted in a wave of emigration, while the suppression of the “Prague spring” in 1968 gave rise to another.

During the communist period, over 500,000 people emigrated from Czechoslovakia, mostly in two main waves (after February 1948 and August 1968). This was in turn followed by a new wave of emigration during the period of political liberalization preceding the Prague spring.

The number of emigrants had started to increase gradually since 1964. During the period from1960 to 1969, about 44,000 people emigrated from Czechoslovakia legally. Most of these people left in 1967, when about 14,000 emigrated. The expected democratization of political life in 1968 had the effect of retarding the emigration process, with the annual number of legal emigrants decreasing slightly to 10,500 people in 1968 and to 9,000 in 1969. The subsequent process of so-called “normalization” brought about a new wave of emigration, as the numbers of emigrants reflected the political expectations of the citizens.

In 1970, about 12,000 people emigrated legally. Later, when the borders were once again more or less closed, the rate of legal emigration slowed down. During the period 1971-1980, a total of nearly 90,000 people emigrated legally. This number fell to just over 30,000 during the period 1981-1990.

The total number of legal emigrants during the whole period from 1970 to 1989 was something under 80,000 people. However, the figure for illegal emigration was undoubtedly higher. The main destinations of legal emigrants from Czechoslovakia during this period were Austria, Germany, Greece and Poland in Europe and the United States and Canada over the Atlantic.

Immigration into the former Czechoslovakia was strictly regulated during the totalitarian period and was relatively low. It consisted mainly of immigration for reasons of family reunion or marriage. The immigrants came principally from the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, as well as from Greece and France. In ethnic terms, many of them were of Czech or Slovak origin. During the communist period, several thousand political refugees received asylum in Czechoslovakia, including some 12,000 refugees from Greece who fled during the civil war over the period 1946-1950.

In 1946 and 1947, about 12,000 Bulgarian agricultural workers immigrated and settled in depopulated areas of the former Sudetenland. Another group of around 4,000 Bulgarians arrived in Czechoslovakia in 1957.

The liberalization of political life in the 1960s in the period preceding the Prague spring also resulted in a rise in immigration. During the decade 1960-1969, approximately 19,000 foreign nationals immigrated to Czechoslovakia, mostly during the years 1966-1968, when over 4,000 people arrived each year. Following the Soviet invasion, the numbers of immigrants decreased slightly during the years 1969 to 1971 to about 3,000 a year. Immigration rose once again during the period of so-called “normalization” from 1970 to 1979, when the total number of immigrants to Czechoslovakia reached nearly 50,000.

The only time when the influence of migration (in the sense of permanent settlement) on the number and composition of the population of the Czech Republic was significant was during the years immediately following World War II. Apart from that period, the annual numbers of immigrants only represented between five and eight per cent of the population losses due to mortality. Immigration therefore only accounted for a fraction of one per cent of the total number of inhabitants and did not have a marked influence on the structure or development of demographic processes.

Gypsies, border Poles and Ukrainians, Koreans and Vietnamese

Gypsies went to the Czech Republic from Slovakia because Communists decided that they must live here (it was an attempt to assimilation). Then, they left our country and traveled to Canada because they had thought that they would not work there. But Canadians don’t want them because there were moving too many of them. Therefore, they impose visas for Czech Republic, with a view that gypsies will not be able to move there.

Border Poles and Ukrainians were abused because they were very poor and they needed jobs. They were working in the worst conditions and they got always less money than other people did.

Communists invited here workers from Cuba and Vietnam. They could work here in our socialistic country but only sometime. After the time for workers ended, they had to leave our country and went home.

Bibliography

Wikipedia – The Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/

Part One (“Introduction” and “Migration in France”) has been written by the students of the 1st class ES from the Aristide Bergès High School, under the guidance of the teachers Nicole Clapié, Alain Croquelois, Martine Dupuis and Françoise Sainte-Rose.

Part Two (“History of Italian migration from 1900 to today”) was realized by the students of the classes IV A and IV G from the "Galileo Galilei" Scientific High School (Maria Salbini, Rocco Ciola, Giulio Lisanti, Noemi Miglionico, Luca Romano, Walter Mancino), coordinated by the teachers Antonella Santagata, Giuseppe Dilillo, Annamaria Garramone, Elisabetta Grimaldi, Rosa Marsicovetere, Margherita Viggiano and Mariella Datena.

Part Three (“Chronological Turkish migrations”) represents the contribution of students from Dündar Çiloğlu Anadolu Lisesi (Leyla Betül Feyiz, Fatih Yazgün, Mustafa Toygar Varli, Nurten Bayraktar, Irem Özardiç, Tuğba Kalpak, Ebru Çetin, Pinar Karşiyaka), coordinated by the teachers Pelin Aydın, Melih Yılmaz,Ercan Ayyıldız, Sezgi Poyraz and Selami Arı.

Part Four (“Brief history of migration in Romania”) has been realized by the students from the National College “Constantin Carabella”, coordinating teacher Gabriela Tache.

Part Five (“History of migration in The Czech republic”) has been written by the students of the class 2 C (Barbora Vilišová, Michal Ondruš, Barbora Kalousková, Nina Bajuszová, Sabina Šrámková, Katka Koutníková, Denis Kubajura, Ivana Kadlčíková, Patrik Šimíček, Hana Pastorková) from the Hladnov Gymnasium, under the guidance of Mgr. Martina Baseggio.

No comments:

Post a Comment